Improving Design Assessment for Health Literacy Tools

This paper integrates design guidelines AccessAbility and WCAG with health literacy tools SAM, PEMAT-A/V, and PMOSE/IKIRSH to better assess visual design in health materials. Specifically, the design strategies supplement a more standardized and comprehensive evaluation of spacing, layout, and color schemes in health materials. The suggested evaluation framework offers beginner-friendly advice for health material developers to avoid common design mistakes and improve the design of health materials. This framework can be beneficial for those working independently or for those who cannot access direct support from trained designers due to resource constraints. This framework shows how synthesizing design and health literacy insights can effectively reduce communication issues in public health.

Introduction

Visual design is crucial for making health materials accessible and understandable to patients. Flawed design can impede readability and understandability, or become inaccessible to readers with disabilities (The Association of Registered Graphic Designers of Ontario, 2010). In contrast, thoughtful design in health materials helps readers better retain the information needed for managing their health (Osborne, 2020). Therefore, tackling the public health challenges by improving design can facilitate the process of engaging and communicating with patients (Schwartz, 2016). Currently, many health literacy tools include assessment of design in their scoring criterias (Doak et al., 1996l; Shoemaker et al., 2013). However, these tools exhibit limitations when more qualitative judgements are required for assessing optimal layouts, spacing, and the accessibility of colors in health materials. As a result, insufficiency in design is not always reflected properly in the scoring results of health literacy tools. Additionally, for people working in health literacy, cross-disciplinary collaboration with design professionals can be restricted due to time constraints (Osborne, 2020) or limited budgets. And health material developers without professional training in design can be less sensitive to identifying and avoiding design mistakes. Therefore, a dilemma exists for health literacy developers who want to create better designs yet do not have accessible resources or knowledge to do so.

To address this gap, this paper integrates professional design guidelines with health literacy tools to operationalize the assessment of visual design in health materials. The paper maps gaps in the health literacy tools with strategies from design guidelines to advise on best design practices for health materials. The integration is developed to serve anyone working in health literacy who wants to create better visual design and make materials more accessible and understandable. It especially benefits those who are working independently without the presence of trained designers.

The process discussed in this paper includes examining the scoring criteria of three existing health literacy tools, Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM), the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool for Audiovisual Materials (PEMAT-A/V), and PMOSE/IKIRSH. The specialties of each health literacy tool are introduced below:

SAM assesses the content, literacy demand, graphics, layout and typography, interactivity, and cultural appropriateness of materials (Doak et al., 1996).

PEMAT-A/V assesses understandability and actionability of video or audio contents based on content purposes, word choices, informational organization, layout and design, use of visual aids, and how the materials prompt user actions (Shoemaker et al., 2013).

PMOSE/IKIRSH assess structural complexity and organization of charts (Mosenthal & Kirsch, 1998).

Two professional design guidelines, AccessAbility and Web Content Accessibility Guideline (WCAG) are introduced to operationalize the health literacy tools:

AccessAbility is a design handbook with case studies and graphic design strategies to make print, web, and environments accessible to people of all abilities (The Association of Registered Graphic Designers of Ontario, 2010).

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 is an internationally recognized guideline for making web contents accessible to people with disabilities by using optimal text, image, media, layout, and the presentation of all these components (W3C Web Accessibility Initiatives, 2008).

2. Methods

i. Scoring with Health Literacy Tools

Three materials about birth control were sourced from the CDC Contraception webpage. The materials were evaluated using SAM, PEMAT-A/V, and PMOSE/IKIRSH. The scoring was conducted by the author and an inter-rater for reliability. The selected health materials and the health literacy tools used for evaluation are listed below:

PEMET AV - Planned Parenthood videos on Condom and Birth control pills

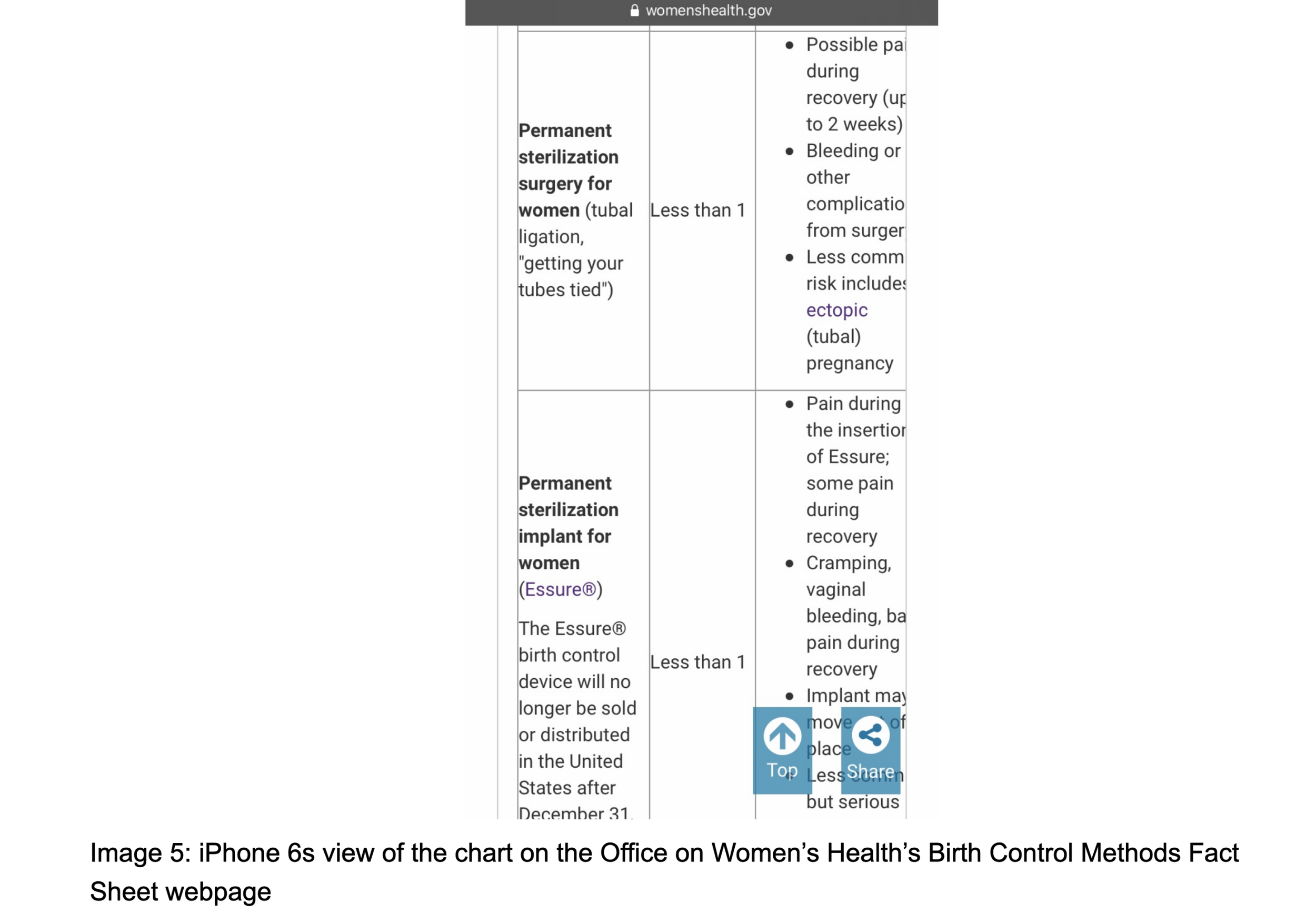

PMOSE/IKIRSH - Office on Women's Health Birth Control Methods Fact Sheet, Specifically, the chart in the dropdown menu of the 3rd question "How can I compare the different types of birth control?"

The scoring was conducted independently by the author and the inter-rater. For consensus purposes, the inter-rater provided a written summary to justify her scoring decisions, debrief her overall experiences with the tools, and explain any gaps found in the tools where design mistakes were not properly assessed. This summary was compared with the author’s scoring decisions, experiences, and identified limitations in the tools. Since this paper focuses on identifying the gaps in health literacy tools, differences in scoring results from the two raters were reviewed with equal weight as a means to discuss the limitations in the tools’ scoring criteria. No further consensus procedures were taken to synthesize the two sets of scoring results into one.

ii. Integrating Design Guidelines with Health Literacy Tools

After assessing the health materials with SAM, PEMAT-A/V, and PMOSE/IKIRSH as well as discussing the tools’ limitations in evaluating design, the health materials were reviewed using design guidelines AccessAbility and WCAG by the author. During this process, design strategies from these guidelines that are helpful for evaluating and improving the design mistakes previously found in health materials were discussed. These design strategies were then mapped to the corresponding assessment criterias from the health literacy tools. The mapping was synthesized in Figure 1, which shows how design strategies can help operationalize the health literacy tools to better assess layout, spacing, and color schemes in health materials.

Additionally, a design inter-rater reviewed Figure 1 and used SAM, PEMAT-A/V, and PMOSE/IKIRSH to score the materials. The design inter-rater provided feedback on their experience of scoring with the health literacy tools and how Figure 1 could impact the assessment and development of design in health materials.

Finally, it’s important to note that as this paper focuses on how health literacy tools evaluate design and how the design guidelines can operationalize the assessment of design by health literacy tools, the process discussed here does not address the readability of proses, the literacy demands, the clarity of contents’ purposes, the sequence and flow of information, the accessibility of presented numeracy, the actionability of materials, the incorporation of motivations, as well as the culturally appropriateness and inclusivity of materials. Therefore, any scoring criterias from the health literacy tools that only focused on these above mentioned subjects are excluded from discussion in this paper.

3. Results

i. Health Literacy Tools Scoring Results

The scoring results of the health materials are shown below:

i. Finding the Gaps of Health Literacy Tools

Based on the scoring results of the 3 materials in SAM, PEMAT-A/V, and PMOSE/IKIRSH, all materials are shown to have a passing score or require less than high school education for comprehension of information. However, the 2 raters found gaps in the 3 health literacy tools, where design mistakes that can impede the accessibility and understandability of materials are not addressed explicitly.

During the assessment process with SAM on the CDC print, both raters identified ambiguity in the assessment for 4a. Layout Factors criteria about whether “adequate white space is used to reduce appearance of clutter”. While the different sections of the material are organized and separated by colored boxes and proper white spaces, there is very limited white space and insufficient organization within each individual section. This causes the contents within some sections to look messy and disorienting for the eyes. This can be exemplified by the “What if the condom breaks” sections (image 1) and the “Dos and Don’t” lists (image 2) of the document.

Similarly, the 4b. Typography criteria receives “adequate” scoring from both raters as it’s considered to have optimal typeface, type size, and typography cues. However, the 4b criteria does not take into consideration the typeface’s line height, which can cause the lack of white space and visual disorganization. For example, both image 1 and image 2 show contents with tight line height, resulting in very little white spaces and condensed text within each section. This can cause difficulties for the reader to keep track of the line they are reading when navigating the materials.

During the assessment process of applying PEMAT-A/V for the Planned Parenthood videos, criteria #18 receive a score of 1(“Agree”) from both raters, as both raters agree that “the materials use illustrations and photographs that are clear and uncluttered”. However, one rater identified the illustrations lack color contrast can be imperceptible and inaccessible to people with visual impairment, as exemplified by image 3. But as the appropriate use of colors in illustrations is not assessed by PEMAT-A/V, the scoring fails to reflect color-based inaccessibility of the videos’ graphics.

For the PMOSE/IKIRSH assessment on the Office on Women’s Health’s web-based chart for birth control methods, both raters agree that the chart has low structural complexity for comprehension. However, both raters also identified that consideration of formatting and spacing would improve the visual design of the chart, which is not assessed in the PMOSE/IKIRSH scoring. For example, image 4 shows no white space around the text for some box in the chart.

In addition, when visiting the web page from a smartphone, the contents of the right end of the chart were also cropped out and unreadable (image 5).

iii. Assessing Health Materials with Design Guidelines

Existing accessible design guidelines such as the AccessAbility handbook and the Web Content Accessibility Guideline (WCAG) have included design strategies to optimize spacing, layout and color use for prints and web materials.

Proper Spacing

In the Typographic Readability section of AccessAbility, the handbook explains that when the line height is too tight, the top and bottom of the letters can collide and impede readability. On the other hand, when the line height is too loose, it can cause difficulties for the readers to locate the start of each line, especially if each line is wide. Therefore, AccessAbility suggests a line height at 120% of the type size (e.g. a 12pt font will need an approximately 14.4pt line height) for optimal viewing experiences on print materials. However, the handbook deliberates that the exact number may need to be adjusted depending on the abilities of the target audiences and would be considered in conjunction with other typographic factors that also affect readability. For instance, typefaces that have thicker lines, taller height, or wider width can require more line height to avoid cluttering. As demonstrated in Image 6, at the same font size and line height, font Helvetica Neue 55 looks bigger than Baskerville and Mrs. Eaves. This is due to Helvetica having a bigger x-height (the font height), bigger width, and thicker stroke. This causes a line height at 120% of font size to look more cluttered for Helvetica Neue 55 than the other 2 fonts. Therefore, a line height slightly above 120% would be preferable to optimize its visual presentation.

Similarly, an optimal range of line height is also addressed by Health Literacy Online, a research-based guide for developing accessible health websites and digital tools. Health Literacy Online suggests a line height between 130% to 150% of the font size to maximize readability for websites and digital tools (The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2016). For paragraph spacing, WCAG also suggested that the spacing between paragraphs should be at least 1.5 times larger than the line spacing within the paragraphs.

Therefore, when assessed using AccessAbility and WCAG, the CDC print guide on birth control (image 1 and 2) has insufficient line spacing. Furthermore, the “What if the condom breaks?”” section also has insufficient spacing between paragraphs.

Perceptible Colors

IWCAG addressed the issue of inaccessible color combination identified in the PEMAT-A/V assessment. WCAG analyzes two colors' differences in perceived brightness to assess how perceptible they are to people with visual impairment when placed together. The brightness difference is expressed as a ratio ranging from 1:1, which means the least contrast when white text is on white background, to 21:1, which has the most contrast when black text is on white background. An automated online tool Color Contrast Ratio is developed by Lee Verou to calculate this contrast ratio for two colors. WCAG suggested that for un-bolded text smaller than 18pt and bolded text bigger than 14pt, there should be a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1 between the text and background. For unbolded text bigger than 18pt and bolded text bigger than 14pt, a contrast ratio of at least 3:1 between the text and the background is recommended. Additionally, icons or visual aids should have a contrast ratio of at least 3:1.

For example, pure red has a ratio of 4:1 when placed on whie background, meaning that it’s only suitable as text colors when the text is bolded and bigger than 14pt, or unbolded and at latest 18pt, or for icons. Pure green has a very low contrast ratio of 1.4:1, meaning that it’s unsuitable as text color and icon color for white background. Pure blue has a contrast ratio of 8.6:1, meaning that when the background is white, it’s always applicable as icon color and text color.

When assessing the WCAG contrast ratio for visual aids in the Planned Parenthood’s Birth Control Pill video (image 3 from above), a contrast ratio of 1.38:1 is found between the navy blue background and purple outlines for the illustrations (image 7). Therefore, WCAG testifies that the color scheme used in the Planned Parenthood video can be imperceptible for someone with visual impairments. The color scheme in the video thereby fails to comply with the USA government’s accessibility policy which requires sufficient color contrast between foreground and background (USA Government, 2020).

Adaptable Webpage

WCAG also discusses the implementation of liquid layout, which addresses the issues when a web-based chart failed to adapt to the smartphones’ screens (image 5). Liquid layout means the contents and layout of the web page should adapt to screen sizes and browser windows of all widths. Additionally,it means the layout should resize with text size without demanding the user to scroll horizontally for reading a line of text on a full-screen window. When using WCAG to assess the Birth Control Methods webpage, the integration of the chart on the site is considered inaccessible as the text in the right column is cropped on smartphones.

IV. Mapping Design Guidelines to Health Literacy Tools

By using AccessAbility and WCAG to review the health materials, it becomes clear that design strategies from these design guidelines address the assessment criteria from the health literacy tools in more detail from a professional design perspective. Therefore, a mapping of beginner-friendly design strategies and the corresponding health literacy assessment criteria can be synthesized as below:

A second inter-rater knowledgeable about the design also conducted the scoring process independently and provided feedback on Figure 1. The design inter-rater expressed similar concern about SAM failing to address disorganized alignment and messy layout in the Layout and Typography session. Additionally, the design inter-rater also suggested that PMOSE/IKIRSH should consider spacing and layout within each individual item. Overall, the design inter-rater found Figure 1 to be straightforward and understandable to health material creators who are “inexperienced designers”.

4. Discussion

i. Identified Gaps in Health Literacy Tools

During the scoring process, the two raters found that SAM’s scoring results failed to truthfully reflect the improper spacing in the CDC printed guide on birth control and condom. Assessment criteria 4a. Layout Factors about whether “adequate white space is used to reduce appearance of clutter” was considered ambiguous as it does not differentiate between white spaces in between subsections and white spaces within each subsection. For instance, while both raters agreed that there was sufficient white space in-between the subsections of the materials, contents within the subsections were considered cluttered and disorganized. This incoherence throughout the document causes ambiguity for scoring. In addition, assessment criteria 4b. Typeface only focused on the use of typeface, type size, and typography cues, and failed to address how typeface’s line height could contribute to the lack of white space and visual disorganization. Therefore, the scoring process revealed that a more comprehensive evaluation of spacing is required for SAM.

The PEMAT-A/V scoring for Planned Parenthood’s videos on birth control pills and condoms was found to overlook the inaccessibility of color schemes in the video. Specifically, the assessment criteria #18 about whether “the materials use illustrations and photographs that are clear and uncluttered” caused ambiguity. While both raters agreed that the outline designs and purposes of the visual aids and icons were clear, the color schemes used in the videos were measured as imperceptible to audiences with visual impairment. Therefore, a more considerate evaluation of color-based inaccessibility is required for PEMAT’s criteria #18. Similarly, a more elaborate assessment of color schemes can also benefit PEMAT criteria #13 on whether “text on the screen is easy to read” and SAM’s criteria 4b on proper use of typefaces.

Lastly, the PMOSE/IKIRSH scoring for the chart on the Office on Women’s Health’s Birth Control Method Fact Sheet webpage highlighted the needs to implement adaptive layout for charts and all other web-based materials. While the Birth Control Method Fact Sheet chart itself was scored to be low in complexity level and proficiency level, the web interface’s inability to adapt to various screen sizes impeded content readability and accessibility. A more comprehensive evaluation of layout was encouraged for PMOSE/IKIRSH.

ii. Discussion on the Mapping Results

Figure 1’s mapping of design strategies from AccessAbility and WCAG with corresponding assessment criteria from SAM, PEMAT-A/V, and PMOSE/IKIRSH demonstrates how the design guidelines can help operationalize the health literacy tools. Supplementing the health literacy assessment criteria with beginner-friendly strategies on designing for proper spacing, perceptible color schemes, and adaptable web pages can facilitate more comprehensive assessment of visual design in public health.

Based on the review by the design inter-rater, figure 1 serves as a helpful introductory framework for “inexperienced designers” to make better design decisions. Therefore, it can assist health material developers who have no design training to avoid common design mistakes and create better visuals. Specifically, it can benefit those who are working independently without direct support from design professionals, when cross-disciplinary collaboration is limited due to budget or time constraints.

ii. Future Works

The paper only focuses on the assessment of spacing, layout, and color scheme in 4 health materials. However, there are still gaps in the health literacy tools that the paper does not address.

For example, the evaluation of relevant illustration, icons, or visual aids in SAM and PEMAT-A/V can be subjective. This often causes user variability in the scoring results that requires consensus and extra training for the raters. This paper does not specifically cover the best design practices related to these assessment criteria. Future work can be done to map health literacy tools with WCAG’s evaluation of image concepts (W3C Web Accessibility Initiatives, 2008). Additionally, guidelines from non-US countries can be examined to check for international cultural competency. For example, the Accessible Communication Formats developed by the UK government stresses that each image should only show one idea and encourages the integration of jokes and humor (Office for Disability Issues, 2018). Further studies on how to create engaging and informative visual aids for cross-cultural readers can be extremely helpful for the globalizing world.

Furthermore, the chart in the Office on Women’s Health’s Birth Control Fact Sheet has narrow columns (image 4). This demands extra efforts from the readers to frequently jump from one line to the next and can risk disorientation. However, AccessAbility and WCAG do not address ways of optimizing design for overcrowded charts. Therefore, more work can be done to cluttered charts for best reading experiences.

IV. Consensus

During the scoring process, the two raters began by scoring independently. Then the inter-rater provided a written summary to justify her scoring decisions, debrief her experiences with the tools, and explain any gaps she found in the tools that failed to evaluate design mistakes comprehensively. This summary was later compared with the author’s scoring decisions, experiences with the tools, and identified limitations in the tools. This way, the two raters were able to reach consensus about identifying the key gaps in the tools through sharing feedback and raising questions about the tools.

Additionally, consensus among users can also be important for implementing figure 1. The design strategies referenced in figure 1 only provide simplified guidance for preferable design practices in layout, spacing, and color scheme. Depending on the abilities of the targeted users and the purposes of the materials, adjustments may be applied to the design strategies on a case-by-case basis based on discussions among the health material developers. Therefore, it is important to note that while figure 1 aims to standardize the assessment of design as much as possible, there can still be situations where group consensus is encouraged among the users.

V. Next Step

As a next step, Figure 1 needs to be tested out by health material developers to check for any unidentified limitations. If figure 1 can be implemented effectively, it implies that there can be further opportunities to map various health literacy tools with design guidelines for better assessment and development of visual design in public health.

References

Cecilia Conrath Doak, Leonard G. Doak, & Jane H. Root. (1996). Suitability Assessment

of Materials. In Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills (2nd ed., pp. 49–59). J. B. Lippincott Company.

Office for Disability Issues. (2018). Accessible communication formats. UK Government.

Helen Osborne. (2020). Making Lab Test Results More Meaningful (HLOL #175). Health Literacy Out Loud. (No. 175).

Helen Osborne (2020). Creating Materials to Meet Urgent Health Needs (HLOL #201). Health Literacy Out Loud. (No. 201).

Peter Mosenthal, & Irwin Kirsh. (1998). A new measure for assessing document complexity: The PMOSE/IKIRSH document readability formula. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 41, 638–657.

Amy Schwartz. (2016). Design as a Tool for Public Health Innovation. Northwestern Public Health Review.

Sarah J. Shoemaker, Michael S. Wolf, & CIndy Brach. (2013). The Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) and User’s Guide. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The Association of Registered Graphic Designers of Ontario. (2010). AccessAbility: A Practical Handbook on Accessible Graphic Design.

USA Government. (2020). Accessibility Policy. USA Government.

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP). (2016). Health Literacy Online. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

W3C Web Accessibility Initiatives. (2008). Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0. W3C World Wide Web Consortium.